Recently, I have been asked about what software architecture review processes exist to steer architecture work. An architecture review aims at different goals such as finding software design issues early in the development before they get costly. Architecture review processes, for example, formalize different steps. They, furthermore, define input and output to/from architecture reviews. This article describes the different architecture review process approaches.

What are Architecture Reviews and Architecture Review Processes?

An architecture review, in a nutshell, is a mechanism for increasing the likelihood that a software/system architecture will be complete, consistent, and, thus, good [1]. Good software architecture is important, otherwise the development speed can slow down. It can get more expensive to add new features in the future. High internal quality, on the other side, can lead to faster delivery of new features; simply, because there is less cruft to get in the way [2].

Essentially, architecture reviews aim at [1]:

- finding software design problems early in development before they get costly.

- building projects based on best practices and transfer this knowledge across the organization.

- improving the organization’s software quality and operations (-> documentation).

Therefore, architecture review processes formalize different steps, the parties involved, or input and output to architecture reviews. Over the last decades, different architecture review processes have emerged.

Every such process can be modified and adapted to the unique requirements of a specific organization. We will focus on three different prototypical processes that are described in literature:

- The “Classical” Architecture Review process.

- The Architecture Decision Records.

- The Lightweight Request for Comment/Design Document approach.

In the next sections, we will describe these three different prototypical architecture review processes.

The “Classical” Architecture Review Process

The “Classical” Architecture Review process is described by Maranzano et al. in a paper based on common architecture review processes at AT&T, Avaya, Lucent, and Millenium Services [1]. The paper stems from 2005, the idea is based on AT&T’s practices from the late 1980s. A lot of established organizations (still) use this approach in some variation.

Parties

The approach considers three primary parties in an architecture review [1]:

- The project team which requests the architecture review.

- The review team which consists of experts assembled for the review on the basis of their expertise, their independence from the specific project, and their ability to conduct themselves appropriately in a potentially difficult interpersonal situation.

- The Architecture Review Board (ARB) which is a standing team that oversees the review process and its effect on the organization.

Moreover, there are further roles in the overall process—depending on the size of the organization and if these roles are required:

- The review client which is often the project team. The review client pays for the development or is the architecture review’s sponsor.

- The project members who present the architecture to the review team in the process.

- The project management encompasses all the managers responsible for the project’s success.

- The review angel is selected by the ARB being responsible to work with the project team addressing any organizational or political issues that may arise.

- The ARB chair is the architecture review process advocate. The ARB chair is responsible for ensuring the effectiveness of the review.

Process

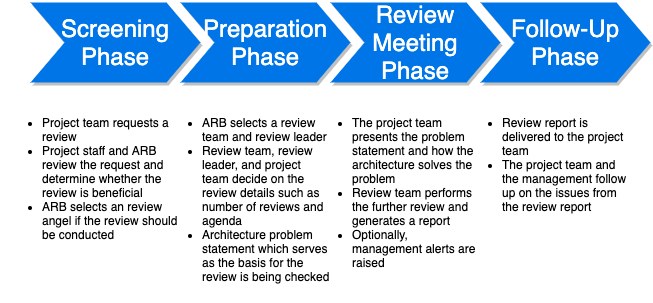

The review process follows four phases [1]. The process is depicted in the figure below.

The Screening Phase starts with the project team requesting a review. The project staff and ARB review the request to determine whether a review would benefit the project. If a review should be conducted, the ARB selects a review angel to oversee the project’s review process.

In the Preparation Phase, the ARB selects a review team and a review leader. Togehter with the project team, they determine the number of reviews and the initial review’s date and agenda. The review team, review leader, project team, and review angel verify that the project which should be reviewed has a clearly defined problem statement (goal) driving the architecture. Furthermore, they check for an appropriate documentation as a basis for the review.

In the Review Meeting Phase, the project team presents the mentioned problem statement and how the proposed architecture solves it. The review team asks further questions to figure out issues they believe could make the project an incomplete or inadequate solution to the problem statement. Afterwards, the review team meets privately and generates a report which is then presented to the project team. Additionally, management alerts can be raised by the review team about problems with the project.

The final phase, the Follow-Up Phase, starts with the review team delivering the final review report to the project team. This should be done within a certain time frame such as 15 days after the review meetings are done. The goal of this phase is to address issues that arose from the review. The project team (and, if a management alert has been raised, the management) must respond to the report within two weeks.

Artifacts

Three different types of artifacts are getting created [1]:

- There are checklists for architects to prepare for the review and checklists for the reviewers to do the review and figure out more of the architecture. The checklists serve as a collection of organizational knowledge and should be maintained.

- There is input to the review. This can be documentation of the system requirements, functional requirements, or informal documentation. The architecture should be designed based on a clear problem statement (goal) tackling the functional and qualitative requirements, the costs, and the timeline.

- There is output from the review such as the review report, an optional management alert letter, an optional set of issues that the project team has to work on.

Conclusion

The “Classical” Architecture Review process is a well-established and formalized process. It is (still) widely used. Especially, bigger organization or, at least, organizations with dedicated architects often make use of this process in some variation.

On the one hand, the formalized process as well as the clear roles within the process help to achieve the goals of architecture reviews. Also, there are different options to vary the process in order to, for example, have less parties involved. In some organizations, there is, for instance, no ARB or review team but an architecture guild (see, e.g.: this article about guilds) which is performing architecture reviews instead. Another option is to reduce the number of artifacts and only give a presentation about the architecture to be reviewed—however, I personally think that there should be a written architecture/design document.

On the other hand, the formalized process and the overall overhead of the “Classical” Architecture Review process is also often the point to be critizied mostly. Running through the overall process, may take too much time for smaller projects or architecture changes which have to be reviewed. In the paper, Maranzano et al. mention that the review preparation time may take up to 6 weeks, the review itself between 1 and 5 days. So, the overhead can be substantial to an organization.

In sum, the entire prototypical approach does not appear to be very agile, but there are also ways to improve the overall process. Nevertheless, it has the potential to balance architectural as well as political aspects in an organiztion.

Architecture Decision Records

Architecture Decision Records (ADR) were initially proposed by Nygard in 2011 in [3]. Nygard stated that architecture in an agile context has to be described and defined differently in comparison to the practice steming from the times before the agile movement. In an agile context, decisions are made step by step alongside the project progress. They will not be made at once, they will also not be made when the project begins. So, the architecture documentation should also be done incrementally. Nygard states that this is also supported by the fact that nobody ever reads large documents [3].

Therefore, Nygard proposes ADR as small documents which concentrate on tracking the motivation, rationale, and consequences behind certain architectural decisions made during different points in time in the project in a very structured and agile way. “We will keep a collection of records for ‘architecturally significant’ decisions: those that affect the structure, non-functional characteristics, dependencies, interfaces, or construction techniques.” (Nygard, 2011) Essentially, the small and structured ADR help to find out about motivation, rationale, and consequences of previous decisions at the time being written and reviewed as well as later on. The ADR form a “decision log” [4].

For more information, we refer to https://adr.github.io/.

Parties

When working with ADR, we can distiguish the following parties:

- The project team/creator(s) of an ADR,

- The ADR reviewer(s)

Process

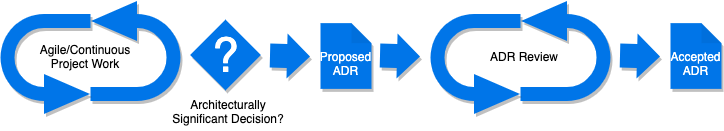

When there is an architecturally significant decision to be made, the project team, the involved architect, or—in general—persons who are involved in the decision making create an ADR. An ADR typically contains 5 sections [3]:

- Title: It is typically describing the architecture decision shortly.

- Status: May be “Proposed”, “Request for Comment”, “Accepted”, or “Superseded”.

- Context: The reasons of the decision to be made.

- Decision: A description of the decision itself and its justification.

- Consequences: The impact of the decision such as the benefits and downsides regarding architecture characteristics, etc.

In general, it is a good idea to let others review an ADR. For that, you use the status of the ADR. A newly created ADR, then, can be in status “Proposed”. When you want other to review the ADR, you can set the status to “Request for Comment”. The ADR can be reviewed by other parties such as other project members, other teams, the (lead) architect, the architecture guild, or persons in the organization who are good in architecture work. As soon as the review is done, the ADR status can be changed to “Accepted” and should be stored somewhere at a public location.

ADR can be stored in GIT or in a wiki. There are tools for managing ADR in GIT, e.g., https://github.com/npryce/adr-tools. In my personal opinion, it is recommendable to store ADR in a public location such as a wiki for better accessibility from an potentially interested audience. However, the tool should be able to track changes to the ADR in a history to identify authors and revert changes if needed. Moreover, a comment functionality for reviewing an ADR is beneficial.

Every ADR and, thus, every decision is an own small document (see also: “Decision log” in the previous section). ADR can get an ID and be referenced in other documentation or wiki pages. New ADR can change aspects of previous ADR. If that happens, they can change the status of the previous ADR to “Superseded”.

Artifacts

The ADR itself is the only artifact in this prototypical architecture review process. Reviews on the ADR should be done on the ADR itself when the ADR is created.

In recent years, different templates have appeared for ADR. In [5], Henderson gathered different ADR example templates. However, ADR can be combined with other ways to document architectures such as Design Documents (see also: Lightweight Request for Comment/Design Document Approach): “A decision record should not be used to try and capture all of the information relevant to an architecture or design topic. […] The creators of an architecture or design should author a document that describes it in detail (whether facilitated by a guild or not).” [6]

Conclusion

ADR are well-suited and widely accepted for documenting architecture decisions [7]. The decision log formed by ADR can be a very essential part to understand the history and the current state of an architecture. Based on the history and the current state, you can make better decisions in the future. ADR and their proposed templates condense architecture decisions to the essential parts. Specifically, when they are stored publicly accessible as a basis for discussions, they are a very good tool for architecture work.

ADR and their strict templates are limited when it comes to the bigger picture of changes. A good ADR should be written neatly and to the point. This, however, may lead to important aspects of changes not being properly described in an ADR. “The ADR is a snapshot of information uncovered during the creation process.” [6] Kuenzli suggests in [6] that also other types of documents should be created in an architecture design process in addition to the ADR. For example, Design Documents can complement ADR. Design Documents are more verbose and capture more information gathered during research phases. The ADR can be created as the outcome of the overall architecture design process.

Lightweight Request for Comment/Design Document Approach

Another approach is the Lightweight Request for Comment (RFC)/Design Document (DD) approach. The approach is called differently by various authors—sometimes Lightweight RFC (or only RFC) and sometimes DD. Ubl [8] and Winters et al. [9] describe it from the perspective of Google (called DD). Orosz mentions the approach in [10] and [11] from the perspective of Uber (called RFC, Lightweight RFC, or DD). Zimmermann [12] and Gonchar [13] mention it from the perspective of Casper (called RFC) and from eBay (called Lightweight RFC). The approach has also been mentioned in the ThoughWorks Tech Radar Vol. 24 trial area as Lightweight RFC approach [14].

Essentially, the Lightweight RFC/DD approach is about writing a DD as the review artifact, sharing this document across the organization, and discussing as well as improving the DD—and the system in design—together with the reviewers. It is a more informal way of documenting software architecture at a certain point in time [8]—originally, considered for the design phase but can be applied to any rework of architectural aspects (solution idea) before the actual (code) work is done.

The approach bases on the strong belief that the community knows more than an individual. Thus, the entire developer community at an organization should be included into the design of the systems. Ubl explains the thoughts behind that nicely in [8]. He states that “[…] it did establish a relatively uniform software design culture across the company [at Google].” [8] Orosz additionally states that the “[…] type of information pushed to people in an organization shapes the culture considerably. […] [It] sets a tone of trust and responsibility.” [10]

On top of that community thinking, the approach considers the power of the written word. “Writing and sharing that writing with others creates accountability. It also almost always leads to more thorough decisions.” [10]

Parties

The DD should be written by the team actually working on the solution idea during the work on finding the solution idea, but before implementating the solution (see also: [8] and [11]).

As soon as the solution idea stabilizes, the DD is shared with the entire organization—or at least with a huge amount of interested people. The interested people should review and discuss the DD and the solution idea to improve it in an open and lightweight process.

Process

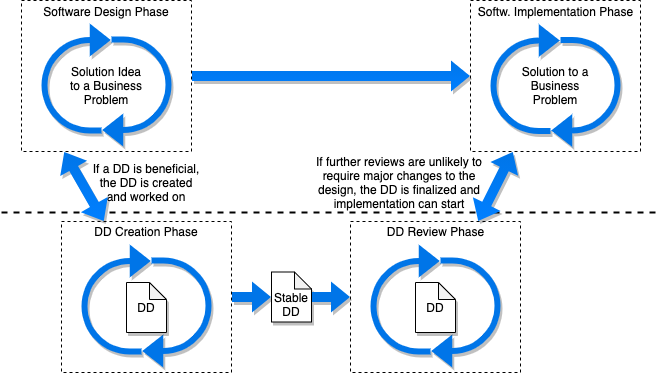

Ubl [8] and Orosz [11] suggest roughly the following process (see: [8] and [11]):

- The team starts with the business problem and brainstorms solution ideas. During that phase, the DD should be started and iterated rapidly within the team itself until the solution idea/DD stabilizes.

- The stable DD should be shared with the organization or, at least, with a wider audience of interested people who review the DD and the solution idea in multiple rounds of feedback.

- “When things have progressed sufficiently to have confidence that further reviews are unlikely to require major changes to the design, it is time to begin implementation.” [8]

Artifacts

The entire Lightweight RFC/DD approach is about the DD. Main goal of the DD is the communication aspect: A DD should identify issues of a solution idea as early as possible in the project lifecycle, help to achieve consensus around a design in the organization, ensure the consideration of cross-cutting concerns, distribute knowledge about solution ideas, and document the solution. In order to achieve that, a certain structure has emerged focusing on architecturally important aspects of a solution idea at Google (see, e.g.: [8]):

- Context and Scope

- Goals and Non-goals

- The actual Design

- System-context Diagram

- APIs

- Data Storage

- etc.

- Alternatives Considered

- Cross-cutting Concerns

Thereby, the template is not fixed and sections are optional depending on the actual solution idea. Also, solution ideas may require other aspects to be described. In general, the DD should focus on the discussion of trade-offs of the solution ideas that were considered during decisions.

“Design docs should be sufficiently detailed but short enough to actually be read by busy people.” [8] Recommendations reach from 1 up to 20 pages depending on the problem and solution idea. As writing a DD is overhead, the decision whether to write a DD comes down to the core trade-off of deciding whether a review is beneficial. If there are benefits in an organizational consensus around a design, a documentation or in having a review from other parties, the extra work of a design doc is worth the effort.

An example DD is available here.

Conclusion

The Lightweight RFC/DD approach is a good way to let the entire organization participate in and improve the design of the organization’s systems. Examples from big software companies such as Google show that this approach works well and can produce good system designs while spreading the knowledge in the organization.

However, the approach requires active participation of people in the organization. Not every organization is ready for such an approach—this may also originate from a different working style or culture such as a very hierarchical organization with a strong and well-established architecture team that does not want to involve other parties.

Another challenge for the Lightweight RFC/DD approach is the question about when a DD should be created and how much work should be put into a DD. Here, an organization needs to allow teams to spend time in writing DD and gathering the feedback. If that is not possible, the entire approach may not work well. Adaptations to the process may prescribe the when to write a DD and how much time for feedback is allowed.

Summary

| “Classical” Architecture Review Process | Architecture Decision Records | Lightweight RFC/DD Approach | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parties | Project team, review team, ARB, and further roles | Project team/Creator(s) of an ADR and ADR reviewer(s) | Project team/Creator(s) of a DD and DD reviewer(s) |

| Process | Well-established and formalized process with four phases (Screening, Preparation, Review Meeting, and Follow-Up Phase). In the different phases, there are different tasks to be done by the different parties (see also: figure about the process). | Process that starts over and over again when there is an architecturally significant decision. When there is an architecturally significant decision, an ADR is created. Afterwards, the ADR is published and reviewed. | Team starts to work on the solution idea to a business problem (Design Phase). During that phase, the DD should be started and iterated rapidly within the team itself until the solution idea and DD stabilizes (DD Creation Phase). The stable DD is shared and reviewed (DD Review Phase). If further reviews are unlikely to require major changes to the design, the implementation of the solution can start (Implementation Phase). |

| Artifacts | Checklists for architects to prepare for the review and checklists for the reviewers to do the review. Furthermore, there is input to the review such as documentation of the system requirements, functional requirements, or informal documentation. Finally, there is the output of the review: review report and optional artifacts such as management alert letters. | The ADR is the main artifact. The ADR can have different states such as “Proposed”, “Accepted”, or “Superseded”. The list of ADR form a “decision log” per project. Moreover, there may be further documentation. | The DD is the main artifact. It is created for a point in time. Additionally, there may be further documentation. |

| Main References | Maranzano et al. [1] published 2005 | Nygard [3] published 2011 and https://adr.github.io/ | Ubl [8] and Winters et al. [9] published 2020 as well as Orosz [11] published 2021 |

References

- J. F. Maranzano, S. Rozsypal, G. H. Zimmerman, G. W. Warnken, P. E. Wirth, and D. Weiss, “Architecture Reviews: Practice and Experience,” Software, IEEE, vol. 22, pp. 34–43, Apr. 2005.

- M. Fowler, “Software Architecture Guide.” Aug-2019.

- M. Nygard, “Documenting Architecture Decisions.” Nov-2011.

- ADR GitHub organization, “adr.github.io - Homepage of the ADR GitHub organization.” ADR GitHub organization, May-2021.

- J. P. Henderson, “Architecture decision record (ADR).” Jul-2021.

- S. Kuenzli, “ADRs are not the only doc in an Architecture process.” May-2019.

- M. Richards and N. Ford, Fundamentals of Software Architecture. O’Reilly, 2020.

- M. Ubl, “Design Docs at Google.” 2020.

- T. Winters, T. Manshreck, and H. Wright, Software Engineering at Google: Lessons Learned from Programming Over Time. O’Reilly UK Ltd., 2020.

- G. Orosz, “Scaling Engineering Teams via RFCs: Writing Things Down.” Aug-2020.

- G. Orosz, “Software Architecture is Overrated, Clear and Simple Design is Underrated.” Apr-2021.

- C. Zimmermann, “RFCs: Lightweight Technical Designs.” Aug-2019.

- G. Gonchar, “Making healthy technical decisions.” Ebay Tech, Apr-2020.

- ThoughtWorks Inc., “Technology Radar Volume 24 - Lightweight approach to RFCs.” Jun-2021.

Acknowledgements

Huge thanks go to Andy Grunwald who helped me to improve this article by reviewing it.