In August/October 2021, we have begun to build a completely new web application which aimed to be a substitution for a former application. When we have started to plan the new application, it was already clear that we wanted to go towards an event-driven application. This article summarizes my impressions and learnings from building this event-driven microservices application in recent months.

The Beginning

Disclaimer: This article presents my personal opinions and perspectives on the project, so this is not my company’s opinion.

When we have started to plan the new application in my company, a corporate startup and 100% subsidary of an insurance company, in August 2021, it was crystal clear that the company is rather not an established company with an established development department and stable processes. There was no team and the idea was to build an entirely new product. In sum, the plans were quite crazy: Our goal was to build an entirely new product as a greenfield project in the Cloud including new processes within only 6 months—start of development should be October 2021. The ultimate deadline was the 29th of March 2022 at which the new product was intended to go live in order to replace the existing application that we inherited from a corporate department of the insurance company.

Essentially, those plans made clear that we should rather use rock-solid technology and architecture to not risk our tight timetable. I remember discussions about monoliths vs. microservices in startups and when to use what (see, e.g.: [1]). Other discussions were around going with a dedicated backend and frontend or not. Eventually, we decided to go towards an event-driven microservice application to leverage flexibility and achieve a pluggable, a loosely coupled application, etc. (see also: [2]; for more details on the architecture, we refer to this section). The following sections tell you more about the entire journey.

The Whole Development in a Nutshell

When we have started with the development in October 2021, we began with creating a domain model (see also: this section). According to Domain-driven Design (DDD), a domain model is a software model of the business domain typically containing well-known nouns of the domain—often implemented as an object model. Such a domain model also acts as a ubiquitous language to improve the communication between software developers and domain experts within a bounded context. The bounded context encapsulates a certain set of assumptions, a common ubiquitous language, and a particular domain model in a coherent environment. It is used for defining conceptual boundaries between applications and/or microservices [3], [4]. In general, there is the rule of thumb that there is one or sometimes more microservice per bounded context, but you should rather not have one microservice dealing with more than one bounded context [5].

We then defined domain events in this domain model collectively. For that, we conducted an event storming workshop with some experts which served as a basis (see also, e.g.: [6], [7]). Following Vaughn Vernon’s definition, a domain event is a record of a business-significant occurrence in a bounded context [3]. In the automotive maintenance (in German: Autoservice) domain of my company, such a record of a business-significant occurrence is, for example, a booking of a service such as an oil change (see also: this section). Concretely, the booking domain event is raised by our microservice handling the backend work of our core booking userflow when a customer books a service. The event is essential for a lot of other services, applications, and departments such as our customer support team which needs to know about the bookings of a customer to handle support cases when a customer calls in. Furthermore, the bookings of a customer are relevant for the management, the product, and the marketing team as well as many more teams to analyze, improve, and advertize our product.

While we were implementing the booking domain event, we have seen soon that such a booking can have different states in our domain such as initially created, paid, upcoming, or finalized. For example, a customer can book a car service (created state) and pay it online via credit card (paid state), but does not show up in the garage. So, the booking stays in the upcoming state and is not finalized. Maybe, the customer then want to get reimbursed. These state changes of the booking domain event, thus, had to be communicated.

Although we had to cross a lot of obstacles during the entire development, we eventually came up with a flexible, loosely coupled, and pluggable solution based on event-driven microservices. The core microservice that emits the booking domain event is not directly connected with the other microservices and systems consuming the event such as the customer relationship management (CRM) system that the support team uses. Everything is decoupled via an event broker (see also: this section). For the CRM system, we, for instance, developed an independent microservice that listen to the domain events and uses the API of the CRM system to make the booking information available to the support team. Another microservice listens to the booking domain events to cummulate business metrics for the product team. Soon, we will implement a data lake to which the booking domain events will also be written to persist them for further analytics.

In the next sections, you can read about further details of the overall solution such as the domain model, the architecture, or the technical perspective on domain events.

The Domain Model

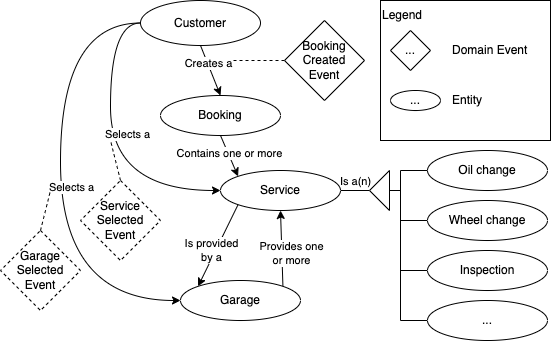

The partial domain model—the full domain model is simply too complex—is depicted in the figure above (it is also freestyled a little bit for the sake of this article). The customer is at the center of our domain model. When the customer wants to book a service she searches for either a garage which provides the services or for the service such as an oil change or a wheel change which is provided by a garage. When the customer selects the garage and the service, she can book the service at the garage—this is the booking domain event (see also: this section).

In general, each connection between two entities in the domain model can reveal an interesting domain event. For example, you may also be interested in the domain event ServiceSelectedEvent or GarageSelectedEvent between the customer and the service respectively the garage entity in your business. We decided to only implement the booking domain event for now, because we had to focus on the essentials. However, we may implement the other domain events soon to better analyze our business.

In sum, the domain model helped us a lot to structure our domain and to come up with relevant domain events. It is also very good when explaining newcomers our domain and the entities they will deal with. Especially, the domain model and, thus, the ubiquitous language helped us to speak more precisely with each other. It helped us to get rid of a lot of synonyms we used in the team.

But when you now want to start your first project with DDD, please be sure to also read about valid criticism. For example, Stefan Tilkov criticizes the hype about DDD in recent years in the two articles [8] and [9]. Furthermore, it can be quite hard to learn DDD—especially, when you want to start off with Eric Evans’ book (see also: [10]). We also did not follow DDD in the purest way when modeling our domain or conducting the event storming workshop—we “freestyled” a lot. So, please always keep in mind that also other system design approaches can lead to excellent results. However, I definitely recommend—like Stefan Tilkov: “Make DDD part of your tool set, but make sure you don’t stop there. There is a life beyond DDD. Not every good design needs to be Domain-driven […]” [9]

The Architecture

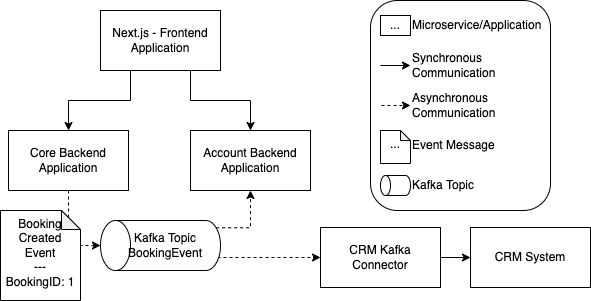

In the figure above, you can see the relevant parts of our architecture of the Autoservice application. The application consists of a Next.js frontend application, two Spring Boot backend applications, an Apache Kafka server as an event broker (see also: [2] for the difference between a message and an event broker) providing topics for the different event messages such as the booking domain event, and a Kafka consumer reading all event messages that should be written to our CRM system.

The frontend application communicates via synchronous REST API calls with the two backend microservices. The backend microservices encapsulate the API for the core booking userflow and the API for the account functionality. For the rest of this section, we concentrate on the core backend microservice.

The core backend microservice encapsulates, as mentioned before, the API for the core booking userflow, so this is the microservice emitting the booking domain event. As described in the previous section (see: this section), the booking domain event is raised when a customer books a service such as an oil change. The booking domain event is sent to a Kafka topic called BookingEvent. Different Kafka consumers are listening to the topic such as the account backend microservice or the CRM Kafka consumer.

The account backend microservice stores the booking domain events per user in the micoservice’s database to show a user her booking history in the account. The CRM Kafka consumer listens to the Kafka topic to store every booking in the CRM system. Here, you can already see that we can plug in a lot of other loosely coupled event-driven microservices to build other functionality in our application. The difficulties come with the management of the domain event messages which is described in more detail in the next section.

Technical Perspective on Domain Events

As mentioned, we decided to go with Kafka as an event broker (see: this section). Following the recommendation of Adam Bellmare in [2], we defined our domain event messages explicitely via Protocol Buffers in a binary format. At the moment, we do not have a schema registry but are using a central repository storing all domain event message definitions. This, in general, works for now. However, we are currently looking at schema registries such as Confluent’s Schema Registry which is also available at Github (see: Confluent Schema Registry for Kafka at Github), because updating all the consumers with new domain event message version is already very cumbersome—even though we do not have so many consumers yet.

In a Goto Conference talk in 2017, Martin Fowler differentiates between four patterns of event-driven architecture [11]:

- Event notifications - the system emitting the event message provides API to get the further data about the event. So, the event-receiving system invokes API of the event-emitting system to handle state changes [11].

- Event-carried state transfer - the event message contains all information about the state change, so the event-receiving system has all the necessary information to react to the state change. In contrast to the event notification pattern, the emitting and the receiving systems can live independently from each other, because the receiving system does not have to call an API to get the event details [11].

- Event sourcing - instead of storing the state of a business entity in a database, event messages are saved in consecutive order in an event store, and the state of the business entity is, then, reconstructed by replaying the event messages from the event store [12].

- Command query responsibility segregation (CQRS) - at the heart of CQRS, is the notion that you can use a different model to update information than the model you use to read information. For more information about CQRS, we refer, for example, to [13] or [14].

In general, our system uses the event-carried state transfer pattern. Thus, the application still uses databases for storing its state, but emits the domain events to Kafka on top of storing the state to the database. This way, we were able to have a fast pace in the project due to not changing the way people think about building software while also benefitting from sending out domain events (see also: this section). With all people with very different background in the entire project, the introduction of domain events was hard enough even without the need to introduce difficult concepts such as event sourcing or CQRS (see also: [11] for criticism about Event Sourcing and CQRS as well as [13] about CQRS). In some use cases, we also use the event sourcing pattern nowadays.

When looking back to the project, it is essential that your team understands what you want to achieve with building event-driven microservices. For example, they need to know what systems you want to integrate to build proper event messages. Furthermore, I recommend that the team should know the four patterns of event-driven architecture. This improves the overall understanding of the entire event-driven architecture and leads to better solutions. For example, the knowledge of the event sourcing pattern improves the solution when building a history of something such as the booking history in our project.

As mentioned already, you should directly think about a schema registry for managing your domain event messages. As soon as the number of microservices increases, you will be happy when you do not have to update all domain event message definitions or coordinate the rollout. Furthermore, your team needs to learn about Protocol Buffers message compatability. A good read about that is, for example, [15].

Last but not least, make sure that your domain event messages are replayable as Adam Bellmare recommends in [2]. For example, our first versions of our Kafka consumers were creating an ID when inserting new entries to some systems. Thus, storing the events was not replayable, because the ID was changing when replaying. Please either create the unique ID in the source system of the event or derive the ID from the event in a deterministic way. Also, consider to use upserts in the destination systems.

Conclusions

In sum, the combination of DDD and event-driven microservices worked well in our project. Building the domain model and defining the domain events based on the domain model, was a good move for the communication within the team. The domain model helped us to be clear about our common (ubiquitious) language and the interdependencies between the entities. Aligning the domain events based on the domain model really helped the developers to understand when the domain event has to be raised.

Currently, we definitely benefit from our event-driven microservices approach when building new integrations, although you already heard about a lot of improvement points such as the schema registry or replayable events. All in all, we are very happy with the choice of going towards an event-driven microservice architecture. The application is—in our opinion—flexible, pluggable, and loosely coupled (see also: this section).

We can definitely encourage you in building such an event-driven microservices application.

References

- S. Tilkov, “Don’t start with a monolith - ... when your goal is a microservices architecture.” 09-Jun-2015.

- A. Bellemare, Building Event-Driven Microservices - Leveraging Organizational Data at Scale. O’Reilly UK Ltd., 2020.

- V. Vernon, Domain-Driven Design Distilled. Addison Wesley, 2016.

- M. Fowler, “Bounded Context.” Jan-2014.

- S. Newman, Monolith to Microservices. O’Reilly, 2019.

- Wikipedia contributors, “Event storming.” Wikipedia, Jan-2022.

- J. Stenberg, “Start with Events and DDD When Building Microservices.” 28-Dec-2016.

- S. Tilkov, “DDD is Overrated.” 01-Mar-2021.

- S. Tilkov, “Is Domain-driven Design overrated?” 02-Mar-2021.

- E. J. Evans, Domain-Driven Design. Addison Wesley, 2003.

- M. Fowler, “The Many Meanings of Event-Driven Architecture.” 2017.

- C. Richardson, “Microservices.io - Pattern: Event sourcing.” 2021.

- M. Fowler, “CQRS.” Jul-2011.

- C. Richardson, “Microservices.io - Pattern: Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS).” 2021.

- J. Gramila, “Protocol Buffers Best Practices for Backward and Forward Compatibility.” 21-May-2021.

Acknowledgements

Huge thanks go to the entire product and development team of HUK-Autoservice as well as our project partners Edenspiekermann and foobar Agency GmbH for the awesome work.